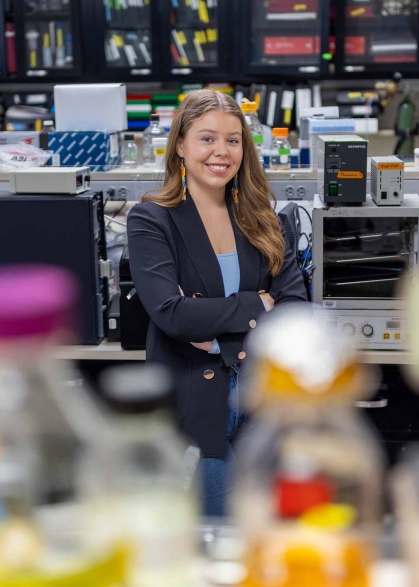

Senior Leaves Her Mark at Rutgers as an Advocate for Indigenous Peoples

Katie Lynch, a biomedical engineering student, spent much of her time at college in leadership roles and representing Native Americans

Between her research and rigorous coursework as a biomedical engineering student, Katie Lynch has dedicated her time to speaking up for Indigenous communities at Rutgers.

The 22-year-old, a citizen of the Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma, is finishing her senior year at Rutgers University–New Brunswick, where she is pursuing a bachelor of science degree in biomedical engineering at the School of Engineering while serving as the president of the RU Indigenous Turtle Island Club, a Native American cultural organization on campus.

As a college student, Lynch helped advocate for the School of Engineering’s publication of a land acknowledgment to recognize the ancestral territory of the Lenape people. During the spring semester of 2022, she and members of the Turtle Island Club held their first large powwow at Vorhees Mall on the College Avenue campus. Moreover, Lynch previously served as president of the Rutgers chapter of the Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science.

“A lot of my leadership on campus has revolved around uplifting Indigenous voices and making sure that we're heard on campus,” said Lynch, who also is a diversity peer educator through the Division of Student Affairs at Rutgers–New Brunswick. “Indigenous students are so often excluded from places of power, and I am incredibly privileged to be in spaces of leadership where I can advocate for those whose voice isn't heard.

“If I can come back in the future and see a thriving Native community here, that’s all I want. I want to build the right ecosystem for others to be able to grow roots. As Native people, community is instilled within us at birth – we can’t survive without each other. I would not be here in this institution without my Native community. It instills me with so much resilience and strength, but also kindness to carry on.”

This advocacy is only part of the impact Lynch has made at Rutgers.

Lynch is the president of the School of Engineering’s student body, vice president of collegiate service organization Circle K International, a former intern of the White House (where she served within the Office of Science and Technology Policy), a 2023 Truman Scholarship nominee and the first Indigenous student in Rutgers history to be recognized by the Udall Foundation as an honorable mention for the Udall Undergraduate Scholarship, which identifies future leaders in environmental, tribal public policy and Native health care fields.

"She lives her truth when she's choosing what to get involved with and when she's making decisions,” said Ilene Rosen, an associate dean at the School of Engineering who meets with Lynch weekly as an adviser for the Engineering Governing Council. “None of it is off the cuff. It is all very well thought out, which isn't to say that she isn't spontaneous and fun, because she is.”

Lynch traces her interest in science back to the seventh grade, when she attended a summer program held by the Monmouth County Vocational School District called “Biotechnology Boot Camp.”

One assignment focused on genetically modified organisms “and we were tasked with creating an idea for our own GMO,” said Lynch, who decided to take a gene from plants that help them withstand cold temperatures and put it into cows “so they could make ice cream that doesn't melt.”

“And that was a big epiphany for me,” the Wall, N.J., resident said. “I was like, wow, if there is possibility to use bioengineering for ice cream, the possibilities to create new health care interventions with the same techniques must be infinite.’”

Lynch found further inspiration for bioengineering while attending Marine Academy of Science and Technology, a magnet high school where she worked with a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist on her senior capstone project: investigating the role of environmental DNA in biodiversity assessments. Lynch, who presented her project at the Jersey Shore Science Fair online, received an honorable mention for her research, which has since been published.

“There are so many facets to this woman,” said Rosen, Lynch’s adviser. “Just the juggling of all she does is pretty amazing. And she's also an excellent dean's list student on top of all that.”

After graduation, Lynch will be pursuing her doctorate degree in health infrastructures and learning systems from the University of Michigan’s Medical School as a Rackham Merit Fellow.

Lynch said she ultimately wants to work at the intersection of public policy, learning health systems and community health science to improve health care access in Indigenous communities.

“My dream would be to go back to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and serve as the policy adviser on Indigenous knowledge,” she said. “For now, I want to use higher education as a form of Native nation building and transform ancestral knowledge into academic excellence.”

If I can come back in the future and see a thriving Native community here, that’s all I want. I want to build the right ecosystem for others to be able to grow roots. As Native people, community is instilled within us at birth – we can’t survive without each other.

Katie Lynch

biomedical engineering student

Lynch said she was drawn to Rutgers–New Brunswick was for its size.

“I went to an extremely small high school, and I really wanted to have the true traditional college experience of the sports and the research and having that all in one place,” said Lynch, whose high school graduating class totaled 66.

She said research opportunities and “engaging in the Douglass Residential College” were draws, too.

“Being able to combine my creativity with science and technology and innovation and use that to create technologies that help people was really my main motivation,” said Lynch, who can’t help but be creative. “I love to paint and draw and do calligraphy.”

Lynch said her “main passion at the moment” is making traditional Native American bead jewelry.

“I've always been a creative person and I come from a really long line of artists in my family,” said Lynch, who has been Irish dancing for much of her life.

Looking ahead, “I plan to continue fighting for Indigenous visibility when I leave this university,” Lynch said. “Whether that means doing community-led research in tribal communities during my doctoral degree or working for a nonprofit advocacy organization, my community is at the heart of everything I do now and will do in the future.”